Step into the enchanting world of Japanese mythology, where ancient deities and gods hold sway over the realms of nature, creation, and the elements. Immerse yourself in the rich tapestry of Shintoism, the indigenous religion of Japan, and discover the profound influence it has on the nation’s mythological beliefs. In this in-depth study, we will explore the historical background of Japanese mythology and delve into the fascinating stories and legends associated with the main deities and gods such as Amaterasu, the powerful sun goddess, Susanoo, the storm god, and Izanagi and Izanami, the creators of the world. Additionally, we will uncover the lesser-known deities like Inari, the fox deity, and Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows. Join us on this captivating journey through Japanese mythology and explore the modern cultural significance and influence it continues to have today.

Contents

- Overview of Japanese Mythology

- Main Deities and Gods

- Lesser-Known Deities and Gods

- Stories and Legends Associated with the Deities

- Modern Cultural Significance and Influence

- Conclusion

-

Frequently Asked Questions

- 1. What is the significance of Shintoism in Japanese mythology?

- 2. Who were Izanagi and Izanami and what was their role in Japanese mythology?

- 3. What is the story behind Amaterasu, the sun goddess?

- 4. How do the gods and deities in Japanese mythology govern nature?

- 5. Who is Inari, the fox deity, and why is she significant?

- 6. What is the role of Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows?

- 7. Why is Hachiman considered the god of war?

- 8. What is the cultural significance of Japanese mythology in modern times?

- 9. Are there any notable stories or legends associated with Japanese deities?

- 10. How can one experience Japanese mythology firsthand?

- References

-

Frequently Asked Questions

- 1. Who is the most important deity in Japanese mythology?

- 2. How did Shintoism influence Japanese mythology?

- 3. What is the historical background of Japanese mythology?

- 4. What are some stories associated with the main deities in Japanese mythology?

- 5. Who is Inari, and why is the deity associated with foxes?

- 6. What does Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows, represent?

- 7. What cultural significance does Hachiman, the god of war, hold in Japan?

- 8. How does Raijin, the god of thunder, influence Japanese culture?

- 9. What role does Uzume, the goddess of joy and laughter, play in Japanese mythology?

- 10. How have the deities of Japanese mythology influenced modern pop culture?

- References

- Read More

Overview of Japanese Mythology

The Overview of Japanese Mythology presents a mesmerizing glimpse into the beliefs, legends, and folklore that have shaped the cultural fabric of Japan for centuries. Rooted in the indigenous religion of Shintoism, Japanese mythology encompasses a vast pantheon of deities and gods who govern various aspects of the natural world and human existence. These mythological tales are characterized by a deep reverence for nature and its elements, reflecting the profound connection between the Japanese people and their environment.

Shintoism, loosely translated as “the way of the gods,” lays the foundation for Japanese mythology. This ancient belief system reveres the kami, the divine spirits that reside in natural elements such as mountains, rivers, and trees, as well as in ancestors and other significant entities. Kami are considered to be both benevolent and mischievous, exerting their influence over all aspects of life.

The historical background of Japanese mythology draws from mythological texts such as the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan). These texts chronicle the creation myths, detailing the story of Izanagi and Izanami, divine siblings who gave birth to the Japanese archipelago and its numerous deities. The mythology also emphasizes the imperial lineage of the mythical Amaterasu, the sun goddess, who is believed to be the ancestor of Japan’s imperial family.

Japanese mythology introduces us to a rich cast of main deities and gods who play integral roles in the mythological stories. Amaterasu, worshipped as the goddess of the sun and the universe, holds immense significance in Japanese mythology. Her radiant presence illuminates the heavens and serves as the ultimate symbol of divinity and power.

Another prominent figure is Susanoo, the storm god, known for his tumultuous nature and his conflicts with his sister Amaterasu. Susanoo’s tempestuous deeds often result in devastating storms, showcasing the dynamic relationship between gods and nature.

Izanagi and Izanami, the creators of the world, also play vital roles in Japanese mythology. Their union gave birth to the islands of Japan and a plethora of deities. However, tragedy befalls them when Izanami dies while giving birth to the fire god, leaving Izanagi to journey to the underworld.

The pantheon of Japanese deities includes gods who govern forces of nature. For example, Raijin, the god of thunder, wields drums to create thunderous sounds and unleash storms. Fujin, the god of wind, controls the winds and is often depicted with a bag containing the winds at his side.

Japanese mythology is not limited to the well-known deities. It also features lesser-known figures who hold unique roles and attributes. One such deity is Inari, the fox deity, revered as the guardian of rice, agriculture, and prosperity. Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows, watches over bodies of water, arts, and knowledge. Hachiman, the god of war, is revered as the divine protector of warriors and samurais.

These captivating mythological tales are entrenched in Japanese culture, inspiring various art forms, literature, and festivals. The stories of deities and gods are often retold through traditional performing arts such as Noh and Kabuki theater. Additionally, shrines dedicated to specific deities dot the Japanese landscape, serving as places of worship and pilgrimage.

The grand tapestry of Japanese mythology continues to be a source of fascination and inspiration, fostering a deep appreciation for nature, tradition, and the enduring power of myth. As we explore the stories and legends associated with these ancient deities, we gain a deeper understanding of the cultural significance and influence that Japanese mythology holds in modern times.

1. Shintoism and Its Influence

Shintoism is an indigenous religion of Japan that has deeply influenced the country’s mythology and cultural beliefs. Rooted in the reverence for nature and the idea of kami, Shintoism encompasses a unique blend of rituals, traditions, and practices that have shaped the Japanese way of life.

The influence of Shintoism can be seen throughout Japanese mythology, where the kami play a central role in the stories and legends. Kami, often translated as “gods” or “spirits,” are believed to reside in natural elements such as mountains, trees, and bodies of water. They are also found in ancestors and significant places.

Central to Shinto belief is the idea of harmony and balance with nature, known as “wa.” This concept manifests in various aspects of Japanese culture, from the architecture of Shinto shrines, which blends seamlessly into their natural surroundings, to the deep respect for the environment and the practice of nature worship. The strong connection between the Japanese people and the natural world stems from their belief in the divine presence of kami.

Shinto rituals and ceremonies are an integral part of Japanese life, be it the celebration of seasonal festivals or the offerings made at household altars, known as kamidana. These practices aim to honor and appease the kami, seeking their blessings and protection for individuals, communities, and the nation as a whole.

Shrines dedicated to specific kami are found throughout Japan, with the most notable being Ise Grand Shrine, dedicated to Amaterasu, the sun goddess. Pilgrimages to these shrines are an important aspect of Shintoism, allowing devotees to connect with the divine and seek spiritual guidance. These shrines serve as cultural landmarks, preserving the rich mythology and traditions of the country.

The influence of Shintoism extends beyond religious practices and rituals. Its impact can be seen in various aspects of Japanese society, including art, architecture, and even the country’s political landscape. The symbolic importance of the emperor in Japan can be traced back to Shinto beliefs, where the emperor is considered to be a direct descendant of Amaterasu, the highest-ranking deity.

The influence of Shintoism is evident in the values and ethics upheld by the Japanese people. Concepts such as respect for others, filial piety, and the importance of community are deeply rooted in Shinto teachings. These principles shape social interactions, familial relationships, and the overall cohesion of Japanese society.

Shintoism’s influence on Japanese mythology is profound and far-reaching. It intertwines with the beliefs, traditions, and cultural practices of the nation, fostering a deep connection between the Japanese people and the divine forces of nature. By understanding the influence of Shintoism, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of Japanese mythology and the enduring legacy it holds.

2. Historical Background of Japanese Mythology

The historical background of Japanese mythology is deeply rooted in ancient texts and oral traditions. Two primary sources provide valuable insights into the mythology of Japan – the Kojiki, also known as the “Record of Ancient Matters,” and the Nihon Shoki, or “Chronicles of Japan.” These texts, compiled during the early 8th century, document the creation myths and genealogies of the imperial family, establishing a historical and mythical foundation for Japanese society.

The Kojiki, completed in 712 CE, is considered the oldest surviving chronicle of Japanese history and mythology. Written in a poetic style, it traces the lineage of the imperial family back to the gods and describes the mythological events that led to the formation of the Japanese archipelago. The Kojiki introduces us to the siblings Izanagi and Izanami, who, upon stirring the ocean with a jeweled spear, gave birth to the islands and a myriad of deities.

The Nihon Shoki, completed in 720 CE, expands upon the narrative found in the Kojiki and provides a more detailed account of Japanese history and mythology. It presents a somewhat more refined version of the creation myth and adds additional stories and genealogical information. The Nihon Shoki was sponsored by the imperial court and served as a tool to legitimize the power and authority of the ruling class.

These mythological texts, although steeped in legend and symbol, also serve as valuable historical records. They shed light on the religious practices, social structures, and political dynamics of ancient Japan. The stories and genealogies within these texts provide a framework for understanding the interconnectedness between gods, humans, and the natural world.

It is important to note that Japanese mythology is not static and has evolved over time. While the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki provide crucial insights into its early form, mythology in Japan continued to develop through folklore, regional traditions, and cultural influences. These ongoing adaptations and reinterpretations contribute to the rich tapestry of Japanese mythology, keeping it alive and relevant in contemporary society.

The historical background of Japanese mythology is a testament to the enduring cultural significance and influence of these ancient stories. It is through the exploration of these myths that we gain a deeper understanding of the values, beliefs, and traditions that have shaped Japan’s unique identity throughout history.

Main Deities and Gods

In the realm of Japanese mythology, the main deities and gods hold great significance and play pivotal roles in shaping the natural world and human existence. These revered figures are deeply interwoven into the mythological fabric of Japan, each possessing unique attributes and powers.

Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, takes center stage as one of the most revered deities in Japanese mythology. She is considered the divine embodiment of the sun, radiating light and warmth to illuminate the world. Amaterasu is believed to be the ancestor of the imperial family, symbolizing the divine lineage and providing legitimacy to the emperor’s rule. Her sacred shrine, located in Ise, is a place of pilgrimage and a testament to the deep reverence for her divine presence.

Susanoo, the Storm God, embodies the tempestuous forces of nature. Known for his wild and unpredictable nature, he frequently clashes with his sister Amaterasu, resulting in tumultuous storms and chaos. Despite his penchant for mischief, Susanoo also possesses the power to slay monsters and bring protection to the people. His intricate relationship with Amaterasu showcases the dynamic interplay between gods and the natural world.

Izanagi and Izanami, known as the Creators, are revered as the divine couple who brought the world into existence. Their union gave birth to the islands of Japan and a host of deities. However, tragedy befalls them when Izanami dies while giving birth to the fire god, prompting Izanagi’s journey to the underworld to retrieve her. Their mythological tale touches upon themes of life, death, creation, and the cyclical nature of existence.

The pantheon of deities also includes Raijin, the God of Thunder. Rumbling across the skies, Raijin wields drums to create thunderous sounds and unleash storms upon the world. He is often depicted as a fearsome figure, further emphasizing the awe-inspiring power of thunder and lightning. Believed to be both a force of destruction and a symbol of renewal, Raijin’s presence embodies the unpredictable nature of the natural elements.

Another powerful deity is Fujin, the God of Wind. Often depicted with a fierce expression and holding a bag containing the winds, Fujin governs the forces of wind and air. He is responsible for the change of seasons, the movement of clouds, and the gentle breeze that whispers through the treetops. Fujin is a reminder of the delicate balance between calmness and destruction that comes with the power of wind.

These main deities and gods form the backbone of Japanese mythology, embodying elemental forces, celestial bodies, and themes deeply ingrained in the culture. Their stories and significance continue to be celebrated and revered, serving as a reminder of the intricate relationship between humans and the divine in Japanese society.

/the-story-of-hercules/

1. Amaterasu – The Sun Goddess

Amaterasu, the revered Sun Goddess, occupies a prominent position in Japanese mythology. She is considered one of the most important deities, symbolizing light, warmth, and the universe itself. Amaterasu is believed to be the ancestor of the imperial family, lending her divinity to the sovereignty of Japan.

According to mythological accounts, Amaterasu was born from the left eye of Izanagi, the creator god. She embodies purity, beauty, and power, and is often depicted with a radiant aura surrounding her. Amaterasu’s realm is Takama-no-Hara, the High Celestial Plain, from where she governs the heavens and illuminates the world with the Sun.

A captivating legend involving Amaterasu revolves around her temporary withdrawal from the world. Troubled by the mischievous deeds of her brother, Susanoo, the storm god, Amaterasu takes refuge in a cave known as Ama-no-Iwato (the Heavenly Rock Cave). Her absence plunges the world into darkness and chaos.

The other gods and deities devised a plan to coax Amaterasu out of the cave. A heavenly dance was performed, accompanied by laughter and merriment. Curiosity eventually overcomes Amaterasu, and she peeks out of the cave, intrigued by the joyful commotion. As she emerges, the gods seize the opportunity to close the cave, ensuring that Amaterasu would not retreat back into darkness.

Amaterasu’s return brings light back into the world. Her resplendent radiance fills the heavens, banishing darkness and restoring order and harmony. This story serves as a metaphor for the cyclical nature of day and night and affirms Amaterasu’s role as the bringer of light and life.

Amaterasu’s influence extends beyond mythology and permeates various aspects of Japanese culture. She is deeply respected and worshipped at the Grand Shrine of Ise, one of the most sacred Shinto shrines in Japan. Her divine presence is celebrated during the annual festival of Amanoiwato Shrine, where participants reenact the events surrounding her emergence from the cave.

Amaterasu’s significance in Japanese mythology is undeniable, as her role as the Sun Goddess represents the eternal struggle between light and darkness, symbolizing hope, renewal, and the tireless pursuit of harmony. Her timeless power continues to inspire and captivate, making her a treasured deity in the rich tapestry of Japanese folklore and belief systems.

2. Susanoo – The Storm God

Susanoo, known as the Storm God in Japanese mythology, is a powerful and enigmatic deity who holds dominion over the storms and natural disasters that periodically ravage the land. He is a complex character, symbolizing both the destructive and transformative aspects of nature.

Susanoo is often depicted as a wild and rebellious god, possessing a fiery temperament and a penchant for causing chaos. His tumultuous relationship with his sister, Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, is legendary. According to myth, Susanoo’s disruptive behavior prompted Amaterasu to retreat into a cave, casting the world into darkness. This event is known as the “Ama-no-Iwato” or “The Heavenly Rock Cave.”

Despite his role in this calamity, Susanoo also plays a significant part in Japanese mythology as a force for good. The Storm God is credited with numerous feats, such as slaying the serpent Yamata no Orochi, an eight-headed, eight-tailed monster that terrorized the land. In this epic battle, Susanoo’s bravery and cunning triumphed, bringing peace and prosperity to the Japanese people.

Susanoo’s connection to storms and the natural elements is further evident in his iconography. He is often depicted with long, flowing hair and carrying a sword, representing his mastery over the tempestuous winds and torrential rains. His association with storms signifies the unpredictability and awe-inspiring power of nature in Japanese mythology.

Legends surrounding Susanoo are not limited to his encounters with other gods. There are tales of his interactions with mortals as well. For example, one story tells of how Susanoo aided a young woman named Kushinada-hime in finding love. He rescued her from a group of monstrous creatures intent on devouring her and ultimately helped her find happiness with a mortal man.

The fascinating mythology surrounding Susanoo has left a lasting impact on Japanese culture. His symbolic representation of storms and his tumultuous relationship with Amaterasu have found expression in various forms of art, literature, and performing arts. The story of Susanoo’s battle with Yamata no Orochi, in particular, is a popular subject in Japanese art and theater.

The tales of Susanoo also resonate with broader themes found in mythology around the world. The dichotomy of destructive and transformative forces in nature can be seen in other mythological figures, such as the Greek god Poseidon, who also wields power over storms and the sea. Exploring these parallels can deepen our understanding of the universal themes present in mythologies across different cultures.

Susanoo, the tempestuous Storm God of Japanese mythology, continues to captivate and intrigue with his complex nature and dramatic stories. His role as a symbol of storms and his tumultuous relationship with Amaterasu highlight the intricate interplay between deities and the natural world. By delving into the intricate details of Susanoo’s mythology, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of Japanese mythological traditions.

3. Izanagi and Izanami – The Creators

Izanagi and Izanami are revered in Japanese mythology as the divine siblings who brought forth the creation of the world and its countless deities. Their story begins with the formation of the Japanese archipelago.

Izanagi, whose name translates to “he who invites” or “he who beckons,” and Izanami, meaning “she who invites” or “she who beckons,” were charged with the task of forming the land. Standing on the floating bridge of Heaven, they used a jeweled spear to stir the primordial sea. As they lifted the spear, drops of brine fell back into the water and formed the first landmass, known as Onogoro Island.

Izanami and Izanagi descended onto the newly formed island and built a grand palace where they performed a sacred marriage ritual, circling around a sacred pillar. It is believed that this act brought forth the numerous deities that would shape the realms of nature, fertility, and the human experience.

However, tragedy befell the divine couple when Izanami gave birth to the fire god, Kagutsuchi. In the process, Izanami suffered severe burns and eventually succumbed to her injuries, descending into the realm of the dead. Grief-stricken, Izanagi ventured into the underworld to bring back his beloved sister-wife.

Upon finding Izanami in the realm of the dead, Izanagi pleaded for her return. But Izanami, who had consumed food from the underworld, was forbidden to leave. Izanagi, unable to accept this, lit a torch to catch a glimpse of his deceased wife. In horror, he witnessed her rotting and maggot-infested corpse. Filled with dread, Izanagi fled from the underworld, sealing the entrance to prevent Izanami from following him.

Izanagi went through a purification ritual to rid himself of the taint from the realm of the dead. As he purified his left eye, the moon goddess Tsukuyomi was born. When he purified his right eye, the sun goddess Amaterasu emerged. Finally, as he washed his nose, the storm god Susanoo was born.

Despite their tragic ending, Izanagi and Izanami’s legacy as the creators of the world and its vast pantheon of deities is etched into Japanese mythology. Their story not only serves as an explanation for the origins of the Japanese archipelago but also explores themes of creation, life, death, and the boundaries between the realms of the living and the dead.

4. Raijin – The God of Thunder

Raijin, the fearsome deity enshrined as the God of Thunder in Japanese mythology, holds a prominent place among the pantheon of gods. Known for his awe-inspiring power, Raijin exerts control over thunder, lightning, and storms, instilling both fear and reverence in those who encounter his wrath.

The portrayal of Raijin commonly depicts him as a muscular figure adorned with a fierce expression. He is often shown wielding hammers, which he vigorously strikes together to create the booming sound of thunder. This imagery symbolizes his ability to conjure storms and unleash bolts of lightning from the heavens.

Worshipped across Japan, Raijin is considered both a protector and a symbol of natural forces. His role as the God of Thunder highlights the deep respect and primal awe that the Japanese hold for the powerful and sometimes destructive forces of nature.

In Japanese folklore, Raijin is believed to be accompanied by a fellow deity named Fujin, the God of Wind. Together, they bring balance to the elements, with Raijin representing thunder and lightning, while Fujin controls the gusts and currents of wind. Their harmonious partnership serves as a reminder of the delicate equilibrium within nature.

The legend of Raijin is intertwined with the traditional belief that the clapping of thunder and the flashes of lightning can ward off evil spirits. This notion led to the practice of clapping hands during thunderstorms, known as “tegashira,” believed to protect oneself from malevolent forces. The cultural significance of Raijin extends beyond mythology and into the daily lives of the Japanese people.

Raijin’s influence is evident in various aspects of Japanese culture. His imagery is often incorporated into art, sculpture, and religious objects, reinforcing his position as a force to be reckoned with. Additionally, his presence is felt during festivals and rituals dedicated to the gods, where thunder drums and percussion instruments are played to invoke his mighty power.

As we glimpse into the realm of Raijin, the God of Thunder, we are reminded of the awe-inspiring forces of nature that shape our world. Through his mythological tales and the reverence with which he is worshipped, Raijin continues to hold a significant place in Japanese culture, symbolizing the untamed power of thunder and lightning.

5. Fujin – The God of Wind

Fujin, known as the God of Wind, holds a significant place in Japanese mythology and is revered for his control over the powerful and ever-changing winds. Depicted as a fearsome deity, Fujin is often depicted with a bag or satchel that contains the winds at his command. His portrayal showcases the awe-inspiring and sometimes destructive nature of wind itself.

Fujin’s origins can be traced back to ancient Chinese mythology, where he was known as Feng Po Po. Over time, his character made its way to Japan and became an integral part of Japanese folklore. As the god of wind, Fujin is responsible for shaping the weather patterns and the force of wind that sweeps across the land.

In Japanese art, Fujin is depicted in various ways. One common portrayal shows him with a green complexion, wild hair, and a disheveled appearance. His attire often incorporates a robe that billows in the wind, emphasizing his association with this natural element. ]]>Astrologically]]>, Fujin is also connected to the zodiac sign of Aquarius, which is associated with the element of air.

Fujin’s significance goes beyond his role as a deity. In Japanese culture, wind has both positive and negative associations. On one hand, wind is seen as a purifying force that can bring change and renewal. It is also associated with movement, freedom, and the power of nature. On the other hand, wind can also be destructive, causing storms and hurricanes. Fujin embodies these dual aspects, symbolizing the unpredictable nature of wind and its potential to bring both blessings and calamity.

In folklore and literature, Fujin often appears as a powerful force in stories and legends. His presence is said to be felt during storms and windy weather. It is believed that Fujin uses his satchel to release wind, unleashing its might on the world. According to some tales, Fujin works in tandem with his brother, Raijin, the god of thunder, creating storms that manifest the full fury of nature’s power.

The worship of Fujin, like many other deities in Japanese mythology, is found in Shinto shrines across the country. These shrines serve as places of reverence and veneration, where people pray for protection from the destructive forces of wind and storms, as well as for blessings of favorable winds for agricultural purposes and travel.

Fujin’s presence extends beyond mythology and religion and can be seen in various aspects of Japanese culture. His image has been incorporated into traditional art forms such as ukiyo-e prints and woodblock paintings. The power and beauty of wind as represented by Fujin have also influenced contemporary art and popular culture, with his likeness appearing in manga, anime, and modern artwork.

Fujin, the God of Wind, stands as a powerful and influential deity in Japanese mythology. His association with wind and the changing forces of nature make him a compelling figure, embodying the dichotomy of creation and destruction that exists in the natural world. Through his worship and representation in various art forms, Fujin continues to captivate and inspire, reminding us of the immense power and beauty found in the ever-shifting winds.

Lesser-Known Deities and Gods

The realm of Japanese mythology is populated not only by the well-known main deities and gods but also by a host of lesser-known figures who hold their own unique roles and attributes.

Inari, the fox deity, takes on a prominent position in Japanese mythology. Often depicted as a fox with multiple tails, Inari is revered as the guardian of rice, agriculture, and prosperity. Considered a benevolent deity, Inari is believed to bring abundance and good fortune to those who pay homage at their shrines. Inari’s shrines are prevalent throughout Japan, with the most famous being Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, which features thousands of vermilion torii gates that form a mesmerizing pathway up the sacred Mount Inari, offering a truly enchanting experience.

Benzaiten, known as the goddess of everything that flows, represents the divine embodiment of water. This lesser-known deity is associated with bodies of water, arts, and knowledge. Often depicted playing a musical instrument, usually a biwa (a traditional Japanese lute), Benzaiten is believed to bring forth creativity and inspiration. Worshippers of Benzaiten offer prayers for artistic endeavors, academic success, and the development of skill sets.

Hachiman, on the other hand, holds a more formidable role as the god of war in Japanese mythology. Considered the divine protector of warriors and samurais, Hachiman was the patron deity of the Minamoto clan, one of the most powerful clans during the Kamakura period. Known for his association with archery, Hachiman became highly revered by samurais and played a crucial role in shaping Japan’s military history. Numerous shrines dedicated to Hachiman are scattered across the country, with Tsurugaoka Hachimangu in Kamakura being one of the most significant.

Uzume, the goddess of joy and laughter, brings a sense of mirth and celebration to Japanese mythology. In the famous myth of Amaterasu’s retreat in a cave, it is Uzume who entices the sun goddess to emerge by performing a lively dance. Associated with the art of entertainment, Uzume is regarded as a source of laughter, happiness, and playfulness. Her role in the mythological narrative highlights the importance of joy and balance in human life.

These lesser-known deities and gods may not command the same level of recognition as their main counterparts, but their presence in Japanese mythology adds depth and diversity to the pantheon. Their unique attributes and stories contribute to the multifaceted nature of the mythology, embodying various aspects of human experience, from agriculture and prosperity to warfare and entertainment. Exploring the lesser-known deities allows us to uncover the intricate layers of Japanese mythology and gain a deeper appreciation for its rich tapestry of beliefs and traditions.

1. Inari – The Fox Deity

Inari is a significant deity in Japanese mythology, renowned as the Fox Deity. Known for their mischievous and mystical nature, foxes have long held a special place in Japanese folklore and culture. Inari, with their association to foxes, possesses attributes that make them an intriguing and multifaceted figure in Japanese mythology.

Inari is widely revered as the guardian of rice, agriculture, fertility, industry, and prosperity. This deity is often depicted as either a male or female figure, sometimes appearing as a young person or an elderly individual. The gender fluidity of Inari represents the deity’s adaptability and ability to transcend traditional boundaries.

The fox, or “kitsune” in Japanese, is a prominent symbol associated with Inari. In Japanese folklore, kitsune are clever and shape-shifting creatures with magical abilities. They are believed to be mischievous tricksters, capable of bewitching humans and bringing both good fortune and chaos. As such, Inari’s connection to foxes represents their ability to bring blessings and transform circumstances.

Inari shrines, known as Inari-jinja, can be found throughout Japan. These sacred spaces are dedicated to the worship of Inari and are often marked by statues or imagery of foxes. These fox statues, known as “kitsune statues,” can range from simple stone carvings to ornately adorned figures. They serve as messengers and protectors, conveying prayers and wishes to Inari.

The worship of Inari is deeply ingrained in Japanese society and culture. Many farming communities pay homage to Inari to ensure bountiful harvests and agricultural prosperity. Inari’s association with rice is particularly significant, as rice has long been a staple food in Japan and holds economic and cultural importance.

Inari’s influence extends beyond agriculture and prosperity. They are also regarded as a patron of business and commerce. Inari is believed to bestow luck and success upon entrepreneurs, merchants, and tradespeople. As a result, many businesses, particularly those related to agriculture and food, have Inari shrines or altars within their premises.

Inari holds a unique place in popular culture, appearing in various forms of media such as manga, anime, and video games. The portrayal of Inari in popular culture often accentuates their mischievous nature and magical abilities, captivating audiences with their supernatural allure.

The worship and reverence of Inari continue to thrive in modern Japan, with devotees seeking blessings, guidance, and protection from this enigmatic deity. Inari’s status as the Fox Deity ensures their enduring presence in Japanese mythology and their role as a symbol of prosperity, fertility, and the mysterious allure of the supernatural.

2. Benzaiten – The Goddess of Everything that Flows

Benzaiten, also known as Benten, is a prominent deity in Japanese mythology, revered as the goddess of everything that flows. Her domain encompasses the realms of water, arts, knowledge, and music, making her one of the most versatile and influential figures in Japanese folklore. Often depicted holding a biwa, a traditional Japanese lute, Benzaiten personifies grace, beauty, and abundance.

Benzaiten’s origins can be traced back to ancient Indian mythology, where she is known as Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge, music, and the arts. Over time, Saraswati’s worship spread to Japan, and she became assimilated into Japanese culture, adapting the name Benzaiten and acquiring additional attributes.

The flowing nature of water is symbolic of the many facets of Benzaiten’s influence. Water represents purification, rejuvenation, and the ebb and flow of life. As the goddess of everything that flows, Benzaiten brings blessings of abundance, prosperity, and fertility. Worshippers often visit her shrines to seek her blessings, particularly in matters related to creativity, learning, and love.

Music is an integral aspect of Benzaiten’s domain. The biwa, which she is frequently depicted with, is a pear-shaped lute with four or five strings. It holds a significant place in Japanese traditional music and storytelling traditions. Benzaiten’s association with music highlights her role as a muse and patroness, inspiring artists, musicians, and poets.

Benzaiten’s influence extends beyond the arts and water. She is also considered a goddess of knowledge and wisdom. The flowing nature of knowledge, like a river, is intimately connected with her domain. Scholars and students often seek her guidance and blessings for academic success and enlightenment.

Throughout history, Benzaiten has been revered in various ways. In Kyoto, the historic city known for its cultural heritage, the Kitano Tenmangu Shrine holds an annual festival dedicated to Benzaiten. This vibrant celebration showcases traditional dances, music performances, and processions in her honor.

The influence of Benzaiten can also be seen in modern times. Her presence can be felt in popular culture, with references to her in manga, anime, and contemporary art. Artists and musicians continue to be inspired by her grace and creativity, channeling her energy into their craft.

Exploring the multifaceted nature of Benzaiten reveals the depth and diversity of Japanese mythology. From her association with flowing water and arts to her patronage of knowledge and music, Benzaiten occupies a significant place in Japanese culture and spirituality. Her timeless appeal continues to inspire and empower individuals, reminding them of the ever-flowing, abundant nature of life.

3. Hachiman – The God of War

Hachiman, revered as the God of War in Japanese mythology, holds a significant place within the pantheon of deities. His origins are believed to be intertwined with Emperor Ojin, a historical figure who was later deified as Hachiman. As the deity associated with martial prowess and protection, Hachiman became deeply venerated as the divine patron of warriors and samurais.

Hachiman’s iconography often depicts him clad in traditional armor with a bow and arrow, symbolic of his role as a skilled archer. He is also sometimes accompanied by a falcon or a dove, representing his omniscient presence and guardianship.

The influence of Hachiman as the God of War extended beyond the realm of battle. He was seen as a unifying force, bringing harmony and stability to the nation during times of war and conflict. Hachiman’s divine protection was believed to bolster the morale of soldiers and lead them to victory.

Throughout history, shrines dedicated to Hachiman have been erected across Japan, often positioned strategically to safeguard territories and honor the deity. One of the most notable is the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine in Kamakura, which was established in the 12th century and became a prominent center of worship.

Hachiman’s association with war also extended to the realm of diplomacy and politics. As the deity believed to influence the fate of the nation, he was called upon during important decisions and negotiations between clans and rulers. His blessings were sought to ensure the prosperity and protection of the land.

Despite his association with war, Hachiman is also revered as a deity of benevolence and compassion. His role as a protector extended beyond the battlefield to encompass the well-being of communities and the nation as a whole. People turn to Hachiman for guidance and assistance in times of crisis and adversity.

The worship of Hachiman continues to endure in present-day Japan, with festivals dedicated to his honor celebrated throughout the year. One prominent festival is the Hachiman Matsuri, held annually at various locations across the country. During these festivities, processions, performances, and rituals take place, encapsulating the traditions and reverence associated with the God of War.

In modern culture, Hachiman’s influence can be observed in various art forms, literature, and media. His legend often serves as a source of inspiration for storytelling, showcasing the values of honor, courage, and loyalty. The legacy of Hachiman, as the God of War, has left an indelible mark on Japanese culture, reminding subsequent generations of the solemnity and heroism associated with armed conflict.

As we delve into the mythology surrounding Hachiman, we gain a deeper appreciation for the historical and cultural significance of this revered deity. His presence symbolizes not only the art of war but also the enduring spirit and resilience of the Japanese people throughout history.

4. Uzume – The Goddess of Joy and Laughter

Uzume, the Goddess of Joy and Laughter, is a delightful and vibrant figure in Japanese mythology. Her presence brings mirth and revelry to both gods and mortals alike, making her an essential deity in Japanese culture.

In ancient tales, Uzume takes center stage during a significant event that involves the sun goddess, Amaterasu. When Amaterasu retreats into a cave, plunging the world into darkness and despair, the other deities desperately seek a way to coax her out. Uzume, with her quick wit and playful nature, devises a plan to bring joy back into the world.

In a theatrical performance like no other, Uzume dances on a nearby tub, creating uproarious laughter from the assembled deities. Her infectious laughter and enticing dance captivate even Amaterasu inside the cave, piquing her curiosity and drawing her out of seclusion to witness the spectacle.

Uzume’s ability to bring joy into the world is symbolic of the power of laughter and its ability to heal and rejuvenate. As the goddess of laughter, she teaches humans the importance of finding joy even during difficult times. Uzume’s presence reminds us to embrace happiness, celebrate life, and find humor even in the darkest of moments.

Uzume’s significance extends beyond mythology and finds its place in various aspects of Japanese culture. She is honored during festivals and celebrations, where her playful spirit is invoked through dance, music, and laughter. The lively performances and the joyous atmosphere created during these events pay homage to Uzume, spreading happiness and fostering unity among the participants.

The story of Uzume serves as a reminder of the power of laughter and its ability to bring people together. Harnessing the energy of laughter can uplift spirits, ease tensions, and foster connections between individuals. Uzume’s role as the Goddess of Joy and Laughter continues to inspire people to approach life with a lighthearted and positive attitude, finding solace in laughter and spreading happiness wherever they go.

Stories and Legends Associated with the Deities

The stories and legends associated with the deities in Japanese mythology are as diverse and captivating as the deities themselves. These tales provide insight into the origins and characteristics of each deity, as well as their interactions with other gods and mortals.

One of the most beloved stories is that of Amaterasu, the sun goddess. According to legend, Amaterasu withdrew into a cave, plunging the world into darkness and chaos, after her brother, Susanoo, went on a destructive rampage. The other gods attempted to coax her out, but it was Uzume, the goddess of joy and laughter, who successfully lured Amaterasu out of the cave by performing a lively dance. This story highlights the power of joy and laughter in dispelling darkness and restoring harmony.

Another fascinating tale involves Susanoo, the storm god, and the giant serpent Yamata no Orochi. In this legend, Susanoo promises to rescue a village from the serpent’s wrath in exchange for the hand of a maiden named Kushinada. With the help of his divine sword, Susanoo slays the serpent and rescues the village, solidifying his reputation as a powerful and heroic deity.

The creation story of Izanagi and Izanami also holds great significance. In this myth, the divine siblings are tasked with creating the world. They stand on the floating bridge of heaven and dip a jeweled spear into the primordial sea, gradually forming the Japanese archipelago. However, tragedy strikes when Izanami dies while giving birth to the fire god. Distraught, Izanagi embarks on a journey to the underworld to retrieve her, only to discover that she has been transformed into a rotting corpse. This tale symbolizes the delicate balance between life and death, creation and destruction.

Another popular legend centers around Inari, the fox deity. Inari is often depicted as a fox, a creature believed to possess magical powers. It is said that Inari has the ability to shape-shift and bring both prosperity and misfortune. People offer prayers and tributes to Inari, especially for bountiful harvests and success in business. The story of Inari showcases the intertwining themes of nature, fertility, and abundance in Japanese mythology.

Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows, is associated with countless intriguing stories. She is often depicted playing a biwa, a traditional Japanese stringed instrument, and has a strong association with music, arts, and knowledge. One legend tells of a mystical encounter between Benzaiten and the famous poet and scholar Sugawara no Michizane, where she imparts wisdom and protects him from harm. This story highlights the profound influence of Benzaiten in the realms of the arts and intellect.

These stories and legends, passed down through generations, form an integral part of Japanese cultural heritage. They not only entertain and captivate but also convey profound lessons and insights about the relationship between gods, humans, and the natural world. As we explore and delve into these mythological tales, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of Japanese mythology and its enduring impact on Japanese society and culture.

Modern Cultural Significance and Influence

The modern cultural significance and influence of Japanese mythology can be witnessed in various aspects of contemporary Japanese society. These ancient tales and beliefs continue to resonate, shaping the arts, entertainment, and even aspects of everyday life.

One notable area where Japanese mythology has left an indelible mark is in literature and popular culture. Numerous novels, manga, and anime series draw inspiration from mythological figures and themes. Works such as “Inuyasha,” “Noragami,” and “Kamisama Kiss” incorporate deities and gods into their narratives, captivating audiences with their blend of fantasy and tradition.

Japanese mythology has also found its way into the world of cinema. Films like “Princess Mononoke” and “Spirited Away” by renowned director Hayao Miyazaki incorporate elements of mythology, emphasizing the interconnectedness between humans and the natural world. These movies have garnered international acclaim and have helped introduce Japanese mythology to a global audience.

In addition to entertainment, Japanese mythology continues to influence various religious and spiritual practices. Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan, remains an integral part of the cultural fabric. Shinto shrines dedicated to specific deities attract worshippers who seek blessings, guidance, and spiritual solace. Matsuri, traditional Shinto festivals, often include rituals and performances that reference mythological tales, keeping the rich traditions alive.

Japanese mythology also plays a role in contemporary art. Traditional Japanese paintings, known as Yamato-e, often depict scenes from mythological stories, showcasing the enduring fascination with these ancient tales. Modern artists incorporate mythological themes into their works, providing a fresh interpretation of the deities and gods.

Beyond the realm of art and entertainment, Japanese mythology has permeated everyday life through various symbols and practices. For instance, the Torii gate, a well-recognized symbol of Shintoism, can be seen at the entrance of many shrines. Omamori, protective amulets, are often adorned with symbols of deities to bring luck and ward off evil spirits. Even the names of weekdays in the Japanese language are derived from mythological origins, emphasizing the ongoing presence of these ancient beliefs.

The influence of Japanese mythology can also be observed in the realm of martial arts. The samurai, who embodied the code of Bushido, drew inspiration from mythological tales of bravery, honor, and loyalty. The concept of the warrior’s spirit, often associated with deities like Hachiman, continues to be revered in modern martial arts disciplines.

Japanese mythology’s enduring presence is a testament to its cultural significance and impact. It serves as a reminder of the deep-rooted connection between the Japanese people and their mystical heritage. As contemporary Japan continues to evolve, the influence of these ancient beliefs remains steadfast, enriching the lives of people both within and beyond the country’s borders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the world of Japanese mythology offers a captivating journey into a rich tapestry of ancient beliefs, deities, and legends. Rooted in Shintoism, Japanese mythology reflects a deep reverence for nature and the interconnectedness between gods and the natural world. The historical background of Japanese mythology, as documented in texts like the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, provides insights into the creation myths and the divine lineage of figures like Amaterasu, Susanoo, and Izanagi.

The main deities and gods of Japanese mythology, such as Amaterasu, Susanoo, and Izanagi, hold significant roles in the mythological stories and serve as symbols of power, creation, and natural forces. The lesser-known deities, like Inari, Benzaiten, and Hachiman, contribute to the diverse tapestry of mythological beliefs, each governing specific aspects of life, nature, and prosperity.

Japanese mythology’s influence can be seen in various aspects of Japanese culture, from traditional performing arts to the presence of shrines dedicated to specific deities. The captivating stories and legends associated with these deities continue to inspire and shape modern cultural practices and beliefs.

By delving into the world of Japanese mythology, we gain not only a deeper understanding of Japan’s history and culture, but also a profound appreciation for the enduring power of myth and its ability to transcend time and connect people to their roots and traditions. The world of Japanese mythology is a treasure trove of wonder and enchantment, inviting us to explore and appreciate the intricate interplay between gods, nature, and humanity.

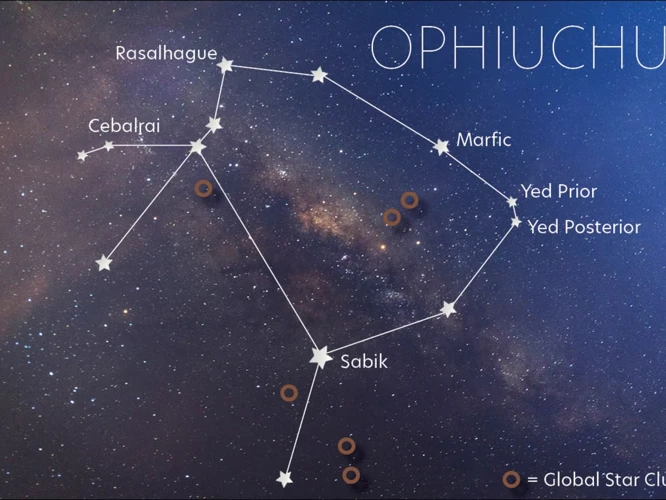

As we conclude this exploration of Japanese mythology, we are reminded of how myths and legends continue to shape our own understanding of the world around us. Just as the deities in Japanese mythology held a significant place in the lives of the people, our own myths and stories help us make sense of our existence and provide meaning to our lives. If you’re interested in delving deeper into the world of mythology, you may find the enigmatic symbolism of Ophiuchus, the lesser-known thirteenth constellation, intriguing. Learn more about it in our article on “/unveiling-enigma-symbolism-ophiuchus/“.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the significance of Shintoism in Japanese mythology?

Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan and serves as the foundation for Japanese mythology. It emphasizes the reverence for kami, the divine spirits found in nature and ancestors, and influences the belief system and traditions of the Japanese people.

2. Who were Izanagi and Izanami and what was their role in Japanese mythology?

Izanagi and Izanami were divine siblings and creators in Japanese mythology. They brought the Japanese archipelago into existence and gave birth to numerous deities. Their union and subsequent journey to the underworld shaped the mythological narrative of creation and life.

3. What is the story behind Amaterasu, the sun goddess?

Amaterasu, the sun goddess, plays a central role in Japanese mythology. According to legend, she withdrew into a cave, plunging the world into darkness due to a conflict with her brother Susanoo. She was eventually lured out by the other deities, bringing light and life back to the world.

4. How do the gods and deities in Japanese mythology govern nature?

The gods and deities in Japanese mythology have dominion over various forces of nature. For example, Raijin, the god of thunder, creates thunderstorms with his drums, while Fujin, the god of wind, controls and directs the winds. They are believed to influence the natural elements and phenomena of the world.

5. Who is Inari, the fox deity, and why is she significant?

Inari is a revered deity in Japanese mythology, often represented as a fox. She is the guardian of rice, agriculture, and prosperity. Inari is associated with abundant harvests and is worshipped to seek success in business ventures and personal endeavors.

6. What is the role of Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows?

Benzaiten holds a significant role in Japanese mythology as the goddess of everything that flows, including bodies of water, arts, and knowledge. She is especially revered by musicians and artists and is associated with creativity and wisdom.

7. Why is Hachiman considered the god of war?

Hachiman is revered as the god of war in Japanese mythology. He is considered the divine protector of warriors and samurais, often associated with military prowess and victory. Many shrines dedicated to Hachiman can be found throughout Japan.

8. What is the cultural significance of Japanese mythology in modern times?

Japanese mythology continues to hold cultural significance in modern Japan. It inspires various art forms, literature, and traditional performing arts like Noh and Kabuki theater. The mythology also plays a role in festivals and rituals, connecting people to their ancestral past and promoting a deep respect for nature and tradition.

9. Are there any notable stories or legends associated with Japanese deities?

Yes, Japanese mythology is replete with captivating stories and legends. For instance, the tale of Susanoo’s battle with the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi is a popular legend. Additionally, Kami, the divine spirits, often feature in tales that depict their interactions with humans and their impact on daily life.

10. How can one experience Japanese mythology firsthand?

To experience Japanese mythology firsthand, one can visit the numerous Shinto shrines scattered throughout Japan. These sacred sites provide opportunities for worship, learning, and observing traditional rituals. Additionally, attending cultural festivals and exploring museums dedicated to mythology can offer deeper insights into this rich and vibrant tradition.

References

- Key Characteristics of Japanese Mythology

- Japanese Mythology – The Mightiest Gods Series 3 – YouTube

- Why Are There So Many Gods in Japan?

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who is the most important deity in Japanese mythology?

The most important deity in Japanese mythology is Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess. She is revered as the ruler of the heavens and the ancestor of the Japanese imperial family.

2. How did Shintoism influence Japanese mythology?

Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan and plays a significant role in Japanese mythology. It shaped the beliefs and practices surrounding the gods and kami (spirits) worshipped in Japan.

3. What is the historical background of Japanese mythology?

Japanese mythology has its roots in ancient oral traditions and folklore. It evolved over centuries, blending native beliefs with influences from Buddhism, Confucianism, and other cultures.

4. What are some stories associated with the main deities in Japanese mythology?

Some famous stories include Amaterasu’s retreat into a cave, Susanoo’s battle against the eight-headed serpent, and Izanagi and Izanami’s creation of the Japanese archipelago.

5. Who is Inari, and why is the deity associated with foxes?

Inari is a deity associated with rice, fertility, and foxes. Foxes are believed to be Inari’s messengers and are seen as guardians of rice fields and crops in Japanese folklore.

6. What does Benzaiten, the goddess of everything that flows, represent?

Benzaiten represents all things that flow, including rivers, music, knowledge, and eloquence. She is one of the Seven Lucky Gods in Japanese folklore and is often depicted playing a biwa (Japanese lute).

7. What cultural significance does Hachiman, the god of war, hold in Japan?

Hachiman is considered the patron god of warriors and the embodiment of samurai virtues. He played a vital role in the unification and military expansion of Japan in ancient times.

8. How does Raijin, the god of thunder, influence Japanese culture?

Raijin is a powerful deity associated with thunder and lightning. In Japanese culture, he is often depicted on temple and shrine guardians to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune.

9. What role does Uzume, the goddess of joy and laughter, play in Japanese mythology?

Uzume is known for her ability to bring joy and laughter to both gods and humans. She is famously credited with coaxing Amaterasu out of her cave and restoring light to the world.

10. How have the deities of Japanese mythology influenced modern pop culture?

The deities of Japanese mythology have had a profound impact on various forms of media, including anime, manga, and video games. Many characters and storylines draw inspiration from these ancient myths and legends.